Wawel Royal Castle Kraków

Wawel 5, 31-001 Kraków

Tourist region: Kraków i okolice

tel. +48 124225155

Over time, the defensive site was built and surrounded by massive fortifications. Evidence of its earliest history is the pre-Romanesque rotunda of the Blessed Virgin Mary.(Saints Felix and Adauctus). For several centuries, Wawel Castle was the seat of rulers from the Piast and Jagiellonian dynasties and of the first elected kings. Although Sigismund III Vasa moved with his court to Warsaw at the end of the 16th century, Wawel's rank did not decline, and the local cathedral remained the coronation and burial place for most Polish kings from then on.

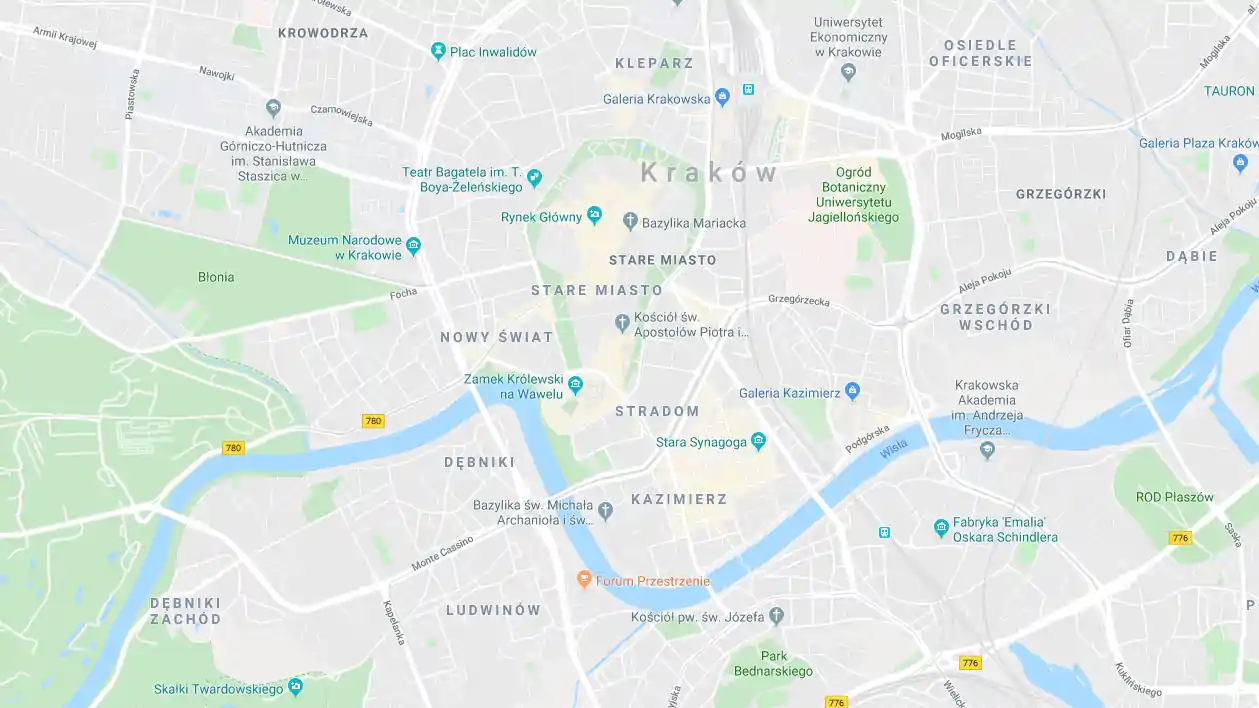

Wawel Castle –the hill above the Vistula River, towering over the waters and marshes, was a safe place for people settling there since the Paleolithic era.

Wawel Castle – a Jurassic limestone rock that dominates the skyline of Kraków (about 228 m above sea level). It was formed about 150 million years ago. Probably from the 7th century onwards, Slavs were there. Early medieval legends tell of a terrifying dragon inhabiting the Wawel cave, of its slayer Krak and his daughter Wanda, who threw herself into the Vistula, refusing to marry a German knight.

At the end of the first millennium, Wawel began to play a role as a centre of political power. In the 9th century, it was the main stronghold of the Vistula tribe. The first historical ruler of Poland, Mieszko I of the Piast family (c. 965–992), as well as his successors,Bolesław Chrobry (992–1025) and Mieszko II (1025–1034), chose it as one of their seats. During that period, Wawel was one of the most important Polish centres of Christianity. The first pre-Romanesque and Romanesque religious buildings appeared on the hill, including a stone cathedral after the Bishopric of Kraków was created in 1000. Wawel became a significant political and administrative centre of the state during the reign of Casimir the Restorer (1034–1058). His son Bolesław the Generous (1058–1079) began the construction of the second Romanesque cathedral, which was not completed until Bolesław the Wrymouth (1102–1138). This ruler divided Poland into districts in his will of 1138, designating Kraków as the seat of the senior prince. In 1291, Kraków, including Wawel, temporarily came under Bohemian rule, and Wenceslas II of the Přemyslid dynasty crowned himself king in Gniezno Cathedral.

In 1306, the Duke of Kuyavia, Ladislaus the Short (1306–1333), entered Wawel and was crowned in 1320 in Kraków Cathedral. This was the first coronation of a Polish ruler on Wawel Hill recorded in the sources. At that time, thanks to Ladislaus the Short, the construction of a Gothic cathedral, the third cathedral temple on this site, was started, the castle was extended, and the wooden and earthen fortifications were replaced with brick ones. Ladislaus the Short's tomb in the cathedral marked the beginning of the tradition of being the burial site for Polish rulers. The last of the Piast dynasty, Casimir the Great (1333–1370), made Wawel into a castle characterised by incredible splendour. In 1364, King Casimir's granddaughter, Elisabeth, married Emperor Charles IV in the extended Gothic castle. The occasion was a famous convention of kings and princes, later taken in by the wealthy burgher Wierzynek.

The accession of Jadwiga of the Hungarian Angevin dynasty to the throne in 1385 and her marriage to the Lithuanian Prince Ladislaus the Short (1386–1434) ushered in another period of Wawel splendour. In addition to local and Western European artists, Ruthenian painters were also employed at the royal court. During the reign of Casimir Jagiellon (1447–1492), the silhouette of the hill was enriched by, among other things, tall brick towers: the Zlodziejska, Sandomierska, and Senatorska. The court of the time was home to Poland's first humanists and teachers of royal sons: the historian Jan Długosz and the Italian Filip Kallimach.

The Italian Renaissance made its debut at Wawel Castle in the early 16th century. King Alexander (1501–1506) and his brother Sigismund I the Old (1506–1548) built a new palace on the site of the Gothic residence, completed around 1540, impressing with an extensive courtyard with columned arcades. Sigismund's artistic patronage was also permanently marked in the cathedral through the erection of the ancestral chapel now known as the Sigismund Chapel by the Florentine Bartholomew Berrecci and through numerous foundations, including a large bell named 'Sigismund’ in honour of the king.Close artistic and cultural contacts with Italy were strengthened by the King's marriage to Princess Bona of the Sforza family in 1518. In addition to Italian artists, German architects, woodcarvers, painters, and founders also worked for Sigismund. The last of the Jagiellons, Sigismund II Augustus (1548–1572), enriched the castle interiors with an excellent collection of tapestries woven in Brussels. During the 'golden' period of Polish culture, Wawel became one of Europe's leading centres of humanism. The reign of Sigismund III Vasa (1587-1632) was significant for the history of the hill, during whose rule, the fire-damaged wing of the building was renovated in the early Baroque style after the castle fire in 1595. The move of the monarch's court to Warsaw resulted in a slow but steady deterioration of the castle's condition. Monarchs stayed in Kraków only occasionally. Attempts were made to remedy the neglect by undertaking repairs under John III Sobieski, the Wettins and Stanislaus II Augustus.

After Poland lost its independence in 1795, the armies of the partitioning states, Russia, Prussia and Austria, successively occupied Wawel, which eventually passed into the hands of the Austrians. The new landlords converted the castle and some other secular buildings into a military field hospital and demolished some buildings, including churches. After the period when the Free City of Kraków (1815–1846) existed, the Austrian army re-occupied the Wawel Hill, transforming it into a citadel that dominated the city. In 1880, a resolution of the Galician Parliament offered the castle as a residence to Emperor Franz Joseph I; the Austrian army left Wawel between 1905 and 1911. At the turn of the 20th century, a significant restoration of the cathedral was carried out, and a little later, the decades-long restoration of the royal castle began.

In Poland reborn in 1918, the castle served as the representative residence of the head of state and a museum of historical interiors. During the Nazi occupation, the Nazi Governor-General Hans Frank lived at Wawel Castle. After the war, the hill hosted a variety of institutions: Wawel State Art Collections (since 1994, Wawel Royal Castle – State Art Collections), the Wawel Royal Castle Restoration Management (until 1985) and the Wawel Metropolitan Basilica Management.

History of the monarch's residence

The ducal seat on the hill was the so-called higher castle, while a town was built in the lower castle with houses for courtiers, clergy and other churches.

The origins of the Wawel residence of Polish rulers are linked to an early Romanesque stone building known as the ‘palatium’ from around the mid-11th century. Its relics have been preserved in the northern wing of the present castle. Over time, the ducal seat on the hill was extended towards the east. Together with the cathedral, it constituted the so-called higher castle (in the lower castle, a town was built with houses for courtiers, clergy, and other churches). In the 14th century, the ruler's residence was considerably expanded by King Ladislaus the Short, and his son Casimir the Great created an impressive Gothic residence consisting of several buildings clustered around an irregular courtyard in the eastern part of the hill. During the reign of Ladislaus the Short, at the turn of the 14th and 15th centuries, the castle was enlarged by adding a Gothic pavilion called the Danish Tower, and in this form, the building survived until the fire of 1499. Around 1504, King Aleksander Jagiellon began rebuilding the residence, giving it a Renaissance look. To this end, he hired the German architect Eberhard Rosenberger from Koblenz and the Italian sculptor and architect François, known as ‘the Florentine’. The work was continued from 1507 by Sigismund I, known as ‘the Old’. Master Francis, the author of the ornate stone bay window in the west wing, erected the east wing before he died in 1516 and began constructing the cloisters. Further work was directed in turn by Master Benedict, the famous Bartholomew Berrecci (creator of the Sigismund Chapel at the Cathedral), and after he died in 1537, was carried out by Niccolo Castiglione and Matteo de Italian . Sculptors and wood carvers – builders of wooden ceilings – worked on the interior decoration: Sebastian Tauerbach and Hans Snycerz, as well as painters who decorated the walls with under-ceiling friezes and created royal portraits. The halls and chambers of the castle were lent splendour by the magnificent Flemish tapestries purchased by Sigismund II Augustus.

The preserved Renaissance building with its beautiful arcaded courtyard, impressive in its grandeur, the spaciousness of its brightly lit interiors and its grandeur, previously unknown on Polish soil, caused a breakthrough in the development of architecture in Poland through the use of architectural forms derived from ancient art. In the 16th century, the castle was the main meeting place for the parliament and senate.

Following a fire in 1595 in part of the castle's north wing, Sigismund III Vasa renovated it in the early Baroque style, employing Italian artists: the architect Giovanni Trevano and the painter Tomas Dolabella. When the royal court settled in Warsaw around 1610, the monarchs visited Wawel only periodically, mainly for weddings, coronations, and funerals, which were held with grand parades. In 1702, during the Swedes' occupation of Wawel, the residence was again severely damaged by fire. Renovated in later periods, it never again reached its original grandeur.

After Poland lost its independence in 1796, the Austrians occupied the castle, adapting it as a military garrison. At the beginning of the 19th century, the cloisters were bricked up as part of the adaptation work. Following the return of Wawel to the Poles and the abandonment of the hill by the occupying Austrian army in 1911, the long-standing restoration of the royal residence began, essentially restoring its original appearance. At first, the action was led by the architect Zygmunt Hendel, from 1916 until the Second World War by Adolf Szyszko-Bohusz, and later mainly by Alfred Majewski. A significant restoration of the castle was carried out again in the last decade of the previous century.

The beginning of the castle's museum collection was the large canvas The Prussian Homage by Jan Matejko, donated by the artist to Wawel Castle in 1882 (now on deposit at the National Museum in Kraków). Exhibits for the museum's renovated interiors were collected through revaluations, purchases, donations and legacies, and the core of the exhibition was the Sigismund Augustus tapestries revived from Russia after 1921 under the terms of the Treaty of Riga. Shortly after the outbreak of the Second World War, the more valuable artefacts, including the tapestries and the Szczerbiec coronation sword, were taken by the Poles to Canada, from where they did not return until 1959–1961. Four permanent exhibitions were then set up, which were systematically expanded to include new objects. In 1994, the museum was enriched by a valuable collection of Italian paintings donated by Karolina Lanckorońska.